WORMS DIGEST

Enya Sullivan

Cute Somerset House

I was definitely in the target audience for Somerset House’s Cute exhibition, as someone who straddles the intersections of both ‘cute’ and ‘goth’ (in which, as Phillipa Snow has already pointed out, there were plenty in attendance). Generally, it feels significant that cuteness has been deemed worthy of its own exhibition, and something that we ought to pay attention to. Sometimes cuteness feels personally disempowering; my own cuteness can make me feel uneasy and misunderstood. However, the show grappled with the affect of cuteness well. It shifts and pulls us in: we feel attracted to it, scared of it, disgusted by it. The parts of the exhibition that explored counter culture (through figures such as Mark Leckey and Juliana Huxtable) and the uncanny elements of cuteness are what pulled me in the most. In an highly instagramable/Tik Tokable (much like elements of the exhibition) and capitalist age where cuteness and its associates (e.g. youth) are used in order to commodify and dull life I think it’s an important reminder that forces are bubbling away behind the ‘cute’, and to see how we can play with the disguise of cuteness to empower others and trick the social order.

In a similar vein, I saw NWAKKE perform at The ICA and was enchanted. She moved around the room with headphones over her ears, looking away from the audience and down at the ground with a deep intimacy. It felt as if I were watching a teenager sing in their bedroom alone. Credits to the ICA’s live team too, who always play around with space and the line between audience and performer so perfectly.

I also want to point everyone’s attention to Parapraxis ongoing online series of texts on Palestine, who state that the essays ‘will engage the colonial politics of Zionism, Palestinian resistance, perennial questions about loss and diaspora, identitarian entanglements with Islamophobia and antisemitism, and more.’ In the first essay, Ugly Enjoyment, Nadia Bou Ali argues that what is happening in Gaza (as we speak now Rafah) shows that the conception of life and rights coined by stale law is explicitly being failed and ignored and that we need to understand life and death beyond this in order to actually save and protect it. Genocide does not pay attention to law or reason, and the state fails to see the legibility of the lives of children and yet we must believe and demonstrate that they persist, as the children do and have done their entire lives in an open air prison.

“I have a reason to live that you do not know. I don’t have a justification, I have no recourse in your normative reckonings with rules and laws, I have no recourse for your theories of justification, yet I am not your irrational form of enjoyment that partakes in the destruction of living. I am a negative value, a pathology that faces you with the very question of what it means to live, to be alive.”

Pierce Eldridge

Bellies by Nicola Dinan was a powerful read for me. I think it’s one of the most heartbreaking novels I’ve read in a long time, but only because so much of the discourse that happens in the novel relates to my experiences of being in a relationship and deciding to transition. There’s something really harrowing about the nuance the novel presents, how trans people run the risk when they are in love of ‘transitioning into loneliness’; meaning, their partner at the time will/could respond with fear, interrogation, or hostility rather than compassion, love, and support. I read this too quickly but I can’t return to it just yet, the sombre place it left me in feels too fresh a wound to poke. If anyone is looking to understand the complexity of relationships that experience and move through transition, this is the one.

I love when Leila Taylor says, ‘Goth-ness for me was always about being open to and curious about the macabre, and death in particular,’ in Christopher Udemezue on Ghost Towns and Goth Sensibilities. I wonder about the way these ideas interface with transness, can we say that trans culture has been aestheticised too? If so, how do we consolidate this, where can we say the origins of transness first began? Jules Gill-Peterson in A Short History of Trans Misogyny writes, ‘Trans is caught between describing a small minority of people and naming something hyper-modern about how the world works.’ If goth is related to melancholy, where might we place the trans? I’ve said it before, but I think the trans is steeped in shame and what is shameful. I don’t mean that to be debilitating, if anything I think it’s rather powerful. A tool we use, shame, to reflect the deplorable presence of structures around us, the fantasies, the realness, the avant garde. I think it also encapsulated the complications of the inner cellular, how code switching between nature and nurture, the oestrogen with the androgen, and the androgen with the oestrogen is complicated by the repression of space (those that we are able to perform within, and those we are not able to exist).

Arcadia Molinas

Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt by Brontez Purnell

I was incredibly excited to get my hands on Brontez Purnell’s new book, out this month with Cipher Press. I’ve admired Purnell’s rawness and hilarity in his writing and beyond since reading 100 Boyfriends and Since I Laid my Burden Down and have such great respect for him as an artist, whose practice covers dancing, music, performance art, zines, writing and probably a lot more.

Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is at once familiar to past readers of Purnell’s books as it is new: in these poems he reckons with his body, blackness and queerness as well as the demands of capitalism, from the perspective of a grown-up artist who’s been in the game for over half his life. “My rage smells like nostalgia / I am / a troubled Negro youth / in his forties / neglecting self-repair / and I am recoiling / the anger in my old man days” he writes in Saturday Day Night Blues. Purnell makes it clear just how familiar he is with the systems and structures that attempt to oppress him, as he is with the mechanisms at his disposal to battle and triumph over them. Brontez Purnell is not one to take shit (throwback to possibly my favorite book dedication of all time which is his one in 100 Boyfriends which reads “Fuck all y’all”). In Diversity Hire he says, “I have come to the conclusion that / I owe you bitches nothing”. He’s constantly “becoming and unbecoming”, a refrain that runs through the poems, reminding us that his identity and practice are in a constant state of flux. Purnell refuses to be pinned down, like his poetry which is defined as ‘genre-defying’ in the back cover. Significantly, he refuses to adhere or give credit to any masticated, structural discourse made to reign over his life, body or sexual encounter. “We remain heroes” he says in the ending of his poem If I Had a Time Machine I Would Kill My Parents.

Racy like always, the absurdity and comedy of life never escapes him. Be prepared to laugh out loud at one verse only to whisper “oh shit” under your breath at the next.

I’ve been attending a book club and writing workshop revolving around the erotic, led by Paulina Flores, the author of the wonderful collection of stories Humiliation translated by Megan McDowell, and the reading list so far has been incredible. I’ve had the chance to revisit some sections from Maggie Nelson’s books The Argonauts and Bluets. I loved discussing the quote she attributes to Leonardo da Vinci in the latter, that goes “Love is something so ugly that the human race would die out if lovers could see what they were doing”, which not only did I really like when I read the book in its entirety myself some years ago, but the discussion surrounding it during the workshop made me see the quote in a new light. Some people mentioned how the decision to reference all these ‘institutional’ white men throughout the book (Wittgenstein is central to The Argonauts) highlighted the lack of language penned by women to voice their own desires and views on the matter of eros and love, a gap which must be filled, by the likes of Maggie Nelson for example. Most importantly however, have been the new discoveries.

Hiromi Kawakami has blown my mind with her sparse, sexy prose. I loved discussing her work in the group, as we picked up on the subtly charged exchanges that happen between friends, the intimacy of friendship and the ‘transgression’ into desire that can take place in those relationships.

Gabriela Wiener has also been a revelation. Her book Sexographies is a collection of articles where she submerges herself, gonzo journalism style, into the world of swingers, egg donation, threesomes and so much more.

Borat by Sacha Baron Cohen

I’m reading a book (more soon) on laughter and how it’s a direct pipeline to our unconscious and in an early section, Sacha Baron Cohen is discussed in relation to his instruction under the master clown Phillipe Gaulier and the uncomfortable truths he reveals through his comedy. The theory the author puts forth is that the type of comedy Sacha Baron Cohen engages in, serves to reveal people’s True Selves and the ugly truths at certain people’s core.

I’d never seen a Sacha Baron Cohen film before (or one where he plays one of his famous/infamous ‘characters’) so I put on Borat and my, oh my, was I blown away. Is that the uncoolest thing to say ever? That in 2023, I think Borat is good? Anyway, I thought it was so good. I think that as a project and artistic performance it has withstood the test of time. Borat as a character has purpose, a moral purpose dare I say, which is that by being a horrible and prejudiced character, he allows other people to feel comfortable in expressing their own prejudice and absurd, horrific takes and views on social matters.

Borat is a journalist from Kazakhstan tasked with making a documentary about the American way of life, with the ultimate goal of strengthening bonds between both countries. His character plays on the stereotypes and assumptions that Americans hold about Arabs and Muslims. In one specifically chilling scene, Borat makes a speech at a rodeo in the South of the country that starts off with “we support your war of terror!” which is met with raucous applause. He continues “May U.S. and A kill every single terrorist!” More cheering. Then, “May George Bush drink the blood of every single man, woman and child of Iraq”. The crowd continues to cheer. And then, he goes to say, “May you destroy their country, so that for the next thousand years, not even a single lizard will survive in their desert.” The crowd flails and looks at each other uncomfortably. I found this speech and train of thought so incredibly prescient concerning the logic that Zionists and Israel sympathisers now follow, that I couldn’t help but respect Sacha Baron Cohen for exposing these poisonous, hateful cognitive dissonances.

As a quick postscript, this viewing launched me into a bit of a Sacha Baron Cohen wormhole and I must say that of the other movies I saw (Brüno and Borat: Subsequent Movie Film) the original Borat is undoubtedly the one that has aged the best and I found the other characters and movies a bit crass and pointlessly provocative. This is not to diminish Baron Cohen’s great skill and courage as an actor, but the rest of his projects seemed a bit mean-spirited in comparison.

Caitlin MCloughlin

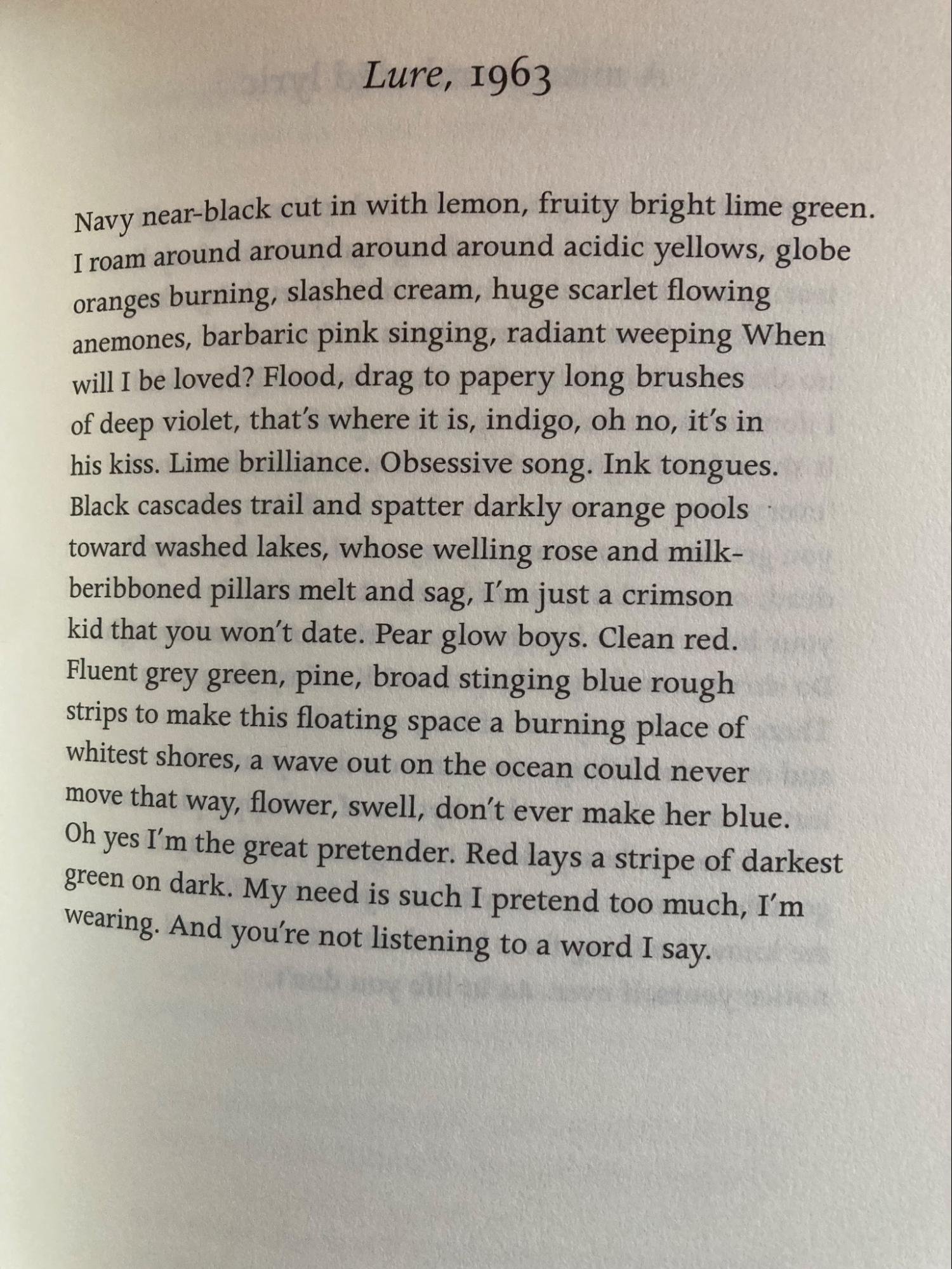

Denise Riley

I’ve been dipping in and out of Denise Riley’s Selected Poems which my friend bought for me for my birthday last year and it’s incrediblleee. This one is one of my faves.

The Weird and the Eerie by Mark Fisher

This book is excellent. A thorough exploration of two ideas that are familiar but by their nature difficult to explain. The weird “involves a sensation of wrongness,” the feeling that accompanies when something of the outside is brought or forcefully materialises in. Whilst the eerie is “constituted by a failure of absence or by a failure of presence. The feeling of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or there is nothing present where there should be something.” What unites both these sensations is that they are not wholly bad (or wholly good); they possess an aesthetics of the ‘bad’ yet they also inspire a kind of fascination or have a certain allure which is perhaps most what is most difficult to explain of all. Fisher uses a long list of novels and films to examine these ideas which as act as a great reading/watch list if you’re looking for some Inspo.

Zone of Interest

I couldn’t speak for an hour after watching this film. I went to see it at Genesis in Mile End and afterwards the whole cinema filed out in a hollowed out silence. It follows Rudolf Höss the commander of Auschwitz and his family as they settle into their SS designated cottage that sits just outside the walls of the concentration camp. The house is bright and airy, spacious and beautifully furnished, but its garden is the real tour de force and the pride and joy of Rudolf’s wife Hedwig. Virid greens, bloody reds and yellows, it buzzes with life and looks almost putrid in its vitality, I felt like I could smell it rotting. The director, Jonathan Glazer, also directed Under the Skin (also amazing) which is incidentally written about by Mark Fisher in The Weird and The Eerie, and whilst the two films are so different, both leave you with a gnawing sense of discomfort, the feeling that something is terribly and palpably wrong – Under the Skin is probably one of the best films I ever seen, but I don’t feel like I need to watch it again. Crucially to the construction of The Zone of Interest, you never see any of the unimaginable horrors that go on within the walls of Auschwitz, they are only inferred by the constant clanking and whirring, the occasional crackle of gun fire or muffled screams, layered over Mica Levi’s sparse but foreboding soundscape. Hedwig is played by Sandra Höller (Sandra in Anatomy of a Fall, which I also loved) who is astonishing, one moment cackling maniacally, the next stomping her foot as Rudolf tells her they might have to be relocated as his career progresses. Small moments of conscience or comprehension are only revealed in moments of seclusion – Rudolf retching on the stairway after receiving a promotion, Hedwig’s mother staring wide eyed out the window as the furnaces light up the night sky a terrible red, by the morning she has left without saying goodbye – in these moments we’re reminded that these character are in fact human, and that is all the more harrowing. This is the cruz of the whole film, this family, who are not just complicit but are active perpetrators in such atrocities are for all intents and purposes a normal, if fairly privileged family, with love for each other and aspirations for the future. In this sense, The Zone of Interest is a not a historical film, but a warning. As Glazer explains “For me, this is not a film about the past. It’s trying to be about now, and about us and our similarity to the perpetrators, not our similarity to the victims.” There is too much I wanna say about this film but I think the best thing would be to go and watch it.