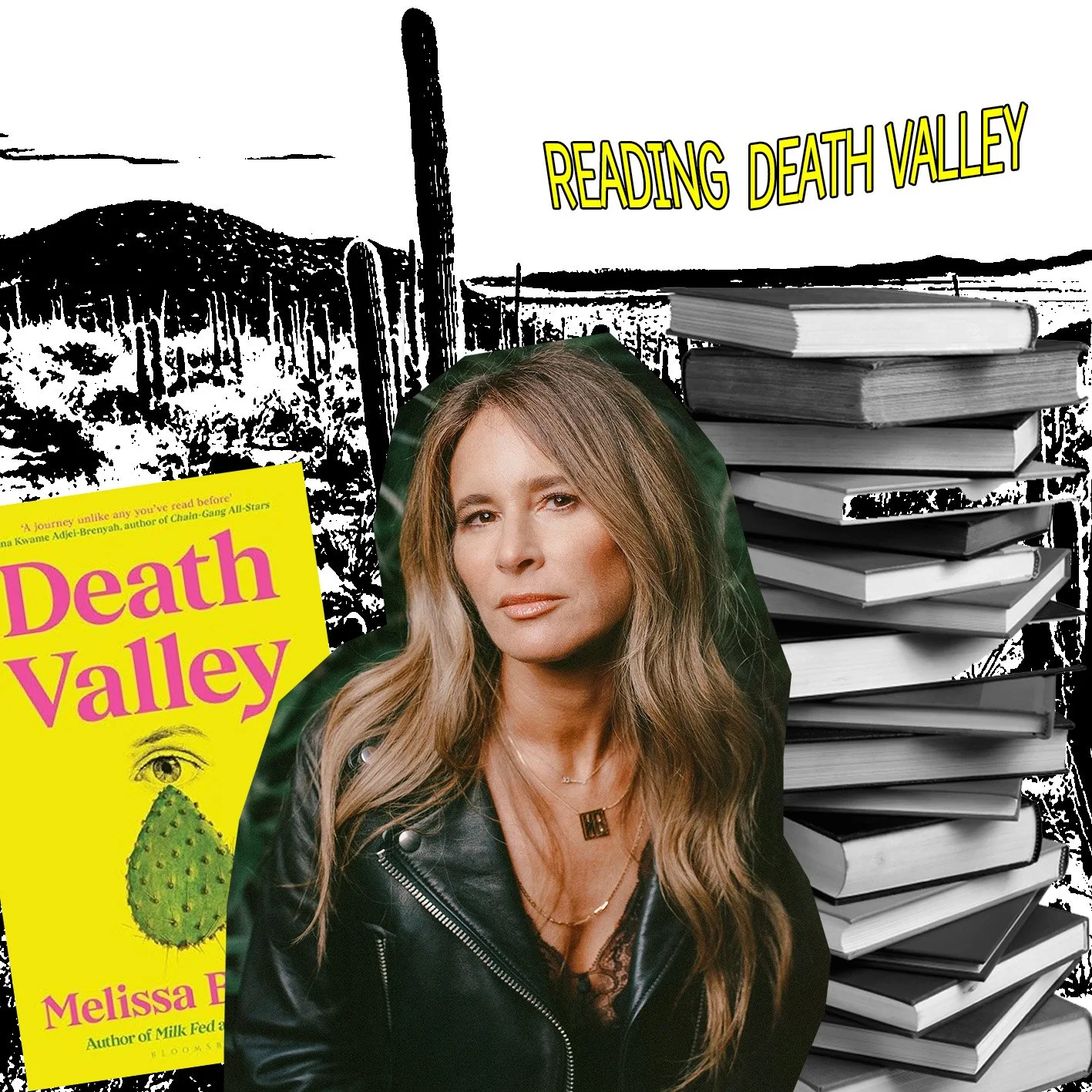

The Melissa Broder Wormhole

From Worms 8 we bring you a snippet of Amelia Abraham’s interview with The Pisces and Milk Fed author Melissa Broder, about her new book Death Valley.

Read an extract of the interview below:

The term “anticipatory grief” has been used in conjunction with the book. Why is that?

The book was inspired by a time when my dad was in hospital in December of 2020 after a car accident. He was in the ICU for six months, and then he died in May 2021. And while he was in the ICU, I said to my friend (whose mom had passed), why do I feel like I'm already mourning my father? He's still alive. I didn't know if he was going to live or die, but I really felt in some ways that he was already gone, or that I could hear him when he wasn't there. She said it’s called anticipatory grief. I thought that my depression and anxiety were having babies, that I was gonna be trapped in this feeling forever. I was scared. Once I gave it a name – anticipatory grief – that gave it shape, and it was helpful for me to know what I was navigating: a loss that had not yet happened. Grief doesn't just pertain to death, it can also be a response to change.

Firstly, I’m so sorry to hear about your father. Do you think anticipatory grief is us trying to do ourselves a favour by grieving something before it happens? Like when you have a breakup and you’re not as sad as you think and you realise you were already mourning the loss before the relationship ended.

Yes, it has a protective element in a way, a psychological defence mechanism. I think it's also something very natural, a sadness about the transience of life. There's something very poignant about knowing that where we are is not where we are always going to be. I love peace, and in moments of peace I want it to last forever, but I know that it won’t. Everything we go through in life is transient. There's something kind of sad about that, right? That not just the hard stuff passes, but the beauty, too. That’s what I was getting at with the ending of Death Valley – the scene where she sees the rose.

Did you find writing cathartic, in terms of your father?

While I was writing it, there was a feeling of connection to my father, almost like he was still alive in some sense, or there was a forward propulsion, something to look forward to. In that way, I think creative investment can feel very much like lifeforce. So when I finished the book, it was hard. The day I sold the book, actually, I was like, why am I not happier? I think there was a real feeling of loss when I finished it.

It’s funny, the character in the book is a writer, and she talks about how on the last page of a book that you write, your characters, they have this arc, and then they get to disappear. Right? But the writer still goes on living with all of life's questions. In Milk Fed, it's not that Rachel has solved her eating disorder and come to some perfect place with her mother, but she has gone through a transformation. In Death Valley, the protagonist arc is less of an arrival. She arrives in this moment with her husband, which as we know, is transient. But that's our last moment with her, so she's forever frozen in that moment. Whereas for the writer, many, many more moments continue to unfold.

For the full interview in Worms 8, get a copy here.

READING DEATH VALLEY

I start reading Death Valley past midnight on Friday the 17th of February. Technically I guess, that means it’s Saturday morning. I’ve just come back from the theatre, where I watched a feel-good play about family with a friend. What I know about Death Valley (from the interview and a quick sweep through Goodreads where I go to update my ‘currently reading’ list) is that it is also about family – but less about feeling good and more about dying. The dedication on the second page reads “to my father” and I think to myself, oh boy, this is going to be a hard one.

The first chapter makes me snort with laughter however, and its ending shocks me with its POV switch revealing the meta-narrative at play, “I’m here at the Best Western for a week under the pretext of figuring out “the desert section” of my next novel.” I’m impressed at how quick Broder sets up the elements at play in this book: there’s writing and its functions, nature in the form of the desert (read desolate, arid, hard, unforgiving, beautiful, spiritual, psychedelic) and the idea of ‘anticipatory grief’. I immediately feel like I’m in good writerly hands.

My first trigger (for this book, I think, is meant to provide solace for those of us dealing with grief, and a trigger is the ringing sound of recognition) comes on the fourth page. The narrator’s dad has been in a car accident that has shuttled him in and out of the ICU for the past five months. Departing from this event, the narrator promptly reflects that, “It is easier to have an intimate relationship with the unconscious than the conscious, the dead than the living”. When my ex-boyfriend died from a car crash four years ago, this exact thought entered my head during the funeral and grieving period immediately after. We’d broken up nearly two years before he died. We were still friends but, like all relationships do, we’d left scars on each other with the claws we’d sharpened over time and with practice. Sartre said it, “Hell is other people.” Upon facing his death, his non-being, the emptiness where he had once been, I realised that my relationship to him would be one-sided from here on out. I found that death had smoothened my relationship with my ex-boyfriend. It felt wrong to reproach a dead person over anything. I felt all my grievances shrink in the immensity and permanence of death. Aside from being disingenuous, this feeling is mired in contradiction because its apparent peacefulness, its smoothened surface, is in direct opposition to death’s uprooting, gut-punching reality. Was remembering only the good, extoling virtues and burying defects a survival mechanism? Did it make grief a lighter burden to bear to only pay witness to the dignified? It is a question I asked myself a lot during those first couple of months without him in the world. Over time I’ve realised that death doesn’t make anyone a saint, even if it feels sacrilegious to defile the dead. There’s more grace in honouring a person for who they were, especially if they brought you conflict. Conflict brings growth, conflict brings change, and that’s what Death Valley gets at the heart of.

I stop reading at around half past one. I sleep deeply and when I wake on Saturday morning, I open the book again over my first cup of coffee of the day. This book is not a sad book about grief, it’s a funny book about it. I appreciate that, I feel that, like the narrator, I have a sturdy belief in the transience of things. This, on most days, brings me peace, even if it can be a hard pill to swallow. Death Valley is concerned with understanding the complexities of change - the one guarantee in life. And the biggest change, if we understand it as a process, is dying. Dying often leads to death, but “Dying is different from death” as the narrator affirms to herself. My own dad isn’t dying. Well, we will all die and are all on our way to death, thus ‘dying’, but presently my dad is not engaged in the act of dying. I think. This is a distinction that Broder unthreads throughout the book and one I’ve come to face in my own life too. Recently, after being engaged in the process of dying for a year, my friend’s dad passed away from a debilitating cancer. Another friend has told me her dad has now been transferred onto palliative care which means he is also engaged in the process of dying. My own dad, I realised recently, is not dying like that. What is happening to him is entirely different. This is a relief, dying is hard. I’m sure that my friends, who remained at their father’s bedside as their vitality sputtered out would say the dying was harder than the death. I think. Who am I to say what their grief feels like? In any case, dying can be monstrous and horrific. Dying can be a steep, painful hill to climb, like the mountains of Death Valley.

I get to about halfway through the book. I put it down, leave the house and head to Marble Arch where the protest in favour of a ceasefire in Gaza is taking place. It is impossible to not think about Palestine if one is thinking about death. We march towards the Israeli embassy and I echo the chants being made in Arabic. The process of dying, when it becomes prolonged, augments the suffering. It is hard to not feel guilty when remembering the dead.

When I wake up on Sunday, I’m tired and hungover and I crawl right back into the bedsheets, cradling Death Valley in my arms. The second half of the book takes a turn for the surreal. The narrator is faced with the unconquerable, desolate landscape of the desert where she must crawl her way through. The desert represents the unknown and to cross it she must be present and “here”. The book, like the narrator, transforms into a desert survival story that reveals the message as a metaphor that lies at the heart of the book:

“Why am I afraid to die? How much more scary can it be? I may be on the way there now. Death. If nothing else: a reprieve from all these heres. Death. A big elsewhere. The biggest elsewhere. Unless, of course, it is another here.”

Broder’s tone throughout remains rational like the above sentiment. Death can be a reprieve. There should be no shame in admitting this. As the narrator encounters the ghosts of her father’s past, she comes to the moving conclusion that, “Of all the languages, I think the greatest is to be there, the greatest of languages, to be here for, to have been there with. Love.” Perhaps it was a feel good book after all.

Arcadia Molinas is the online editor of Worms.