I Love You, Caryl Churchill

- by Jennifer Jasmine White -

In 1967, Roland Barthes declared the death of the author. Literary critics donned mournful shades of black in response. But if the author is dead and buried, why do I yearn for a baseball cap with Annie Ernaux’s name lovingly embroidered into its material? As I dutifully complete doctoral research, why do I find myself getting distracted by dreams of a gossip with Muriel Spark, or a pint with Angela Carter? Writing letters to the authors and artists that make my heart sing allows me to dig a little deeper into this compulsion for parasocial friendship slash hero-worship, and its role in contemporary feminist readership. It forces me to reckon with what I love about a writer, and what it means to do so. In simultaneously gushing and questioning, I shamelessly follow Chris Kraus in the reclamation of the love letter as a critical form.

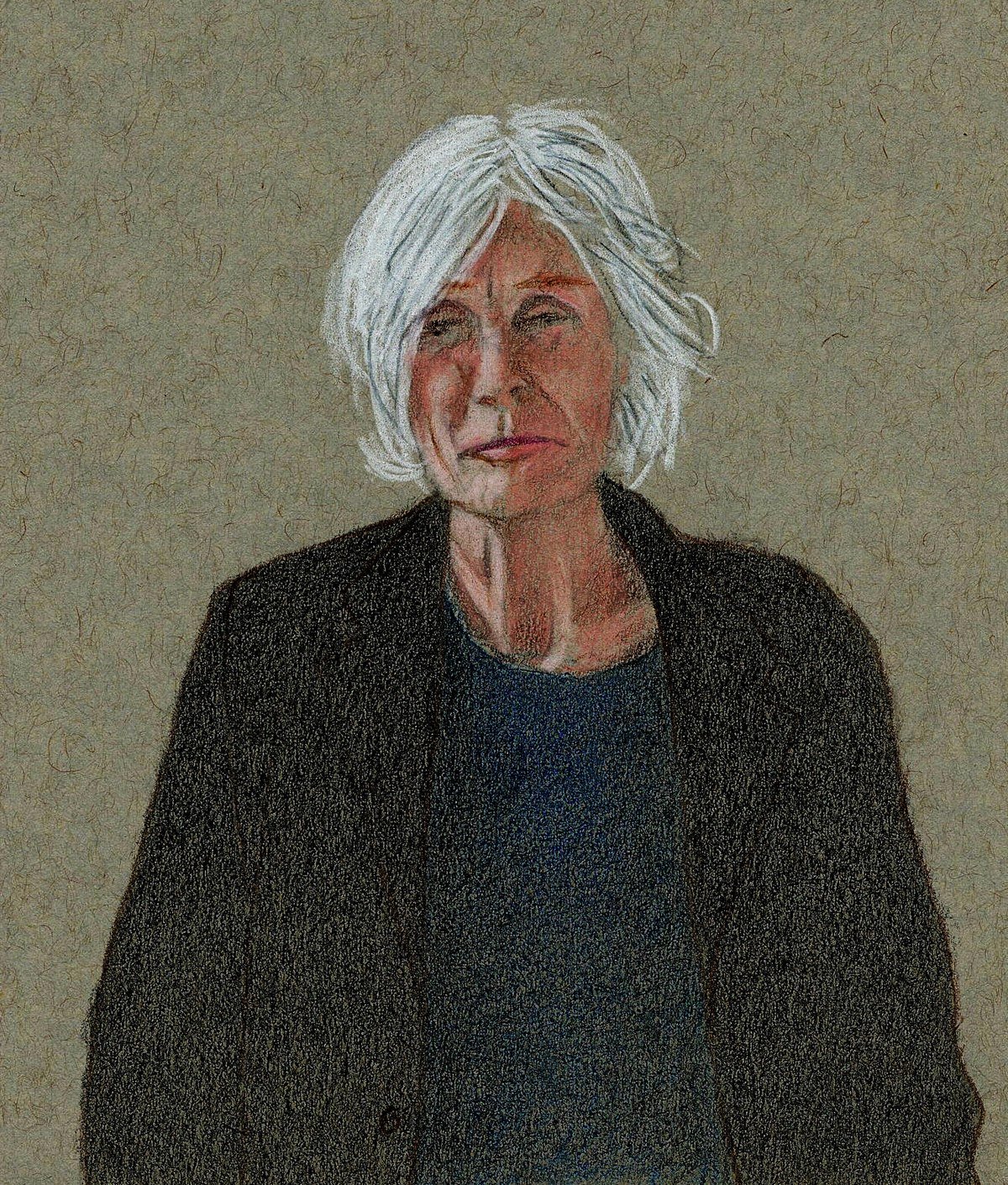

Caryl Churchill has been making radical theatre in Britain since the 1960s. Her works are particularly concerned with gender, ecology, capitalism, and communication. Her most recent show ‘What if Only’(2021) lasted only 20 minutes; the latest in a series of playful experiments with the boundaries of theatrical possibility. Though she has been described both as Britain’s ‘greatest living playwright’ and the ‘patron playwright of feminist killjoys’ her form, her politics and the downright weirdness of her work leave many unfamiliar with her person and oeuvre. Here begins my love letter to Caryl. I’m secretly hoping you might fall head over heels, too.

Dear Caryl,

Last summer, I became obsessed with you. Or at least, with the idea of talking to you. In my defence you were the subject of a pretty hefty dissertation I was writing at the time. There were things I simply had to know. I’ve never really been one for biographical readings, but something about the dazzling ambiguity of your work, and your capacity to reconcile that ambiguity with unwavering political commitment, well, it induced a hunger for answers. It was you who had dreamed up the words and worlds I spent day after day pouring over in the heat of an Oxford summer, and you I yearned to consult. In making a note of the city, I reluctantly admit that my yearning was worsened by the knowledge that you had studied in Oxford too, back in the late fifties. How easy it was to picture us as friends, anti-capitalist interlocutors, collaborators across time. I longed for you to provide some grist for my analysis, or more likely, refute it all entirely. Either would have satisfied me. Isn’t that strange? Unfortunately, you haven’t given an interview since the 1990s. In fact, you’ve given almost no public comment at all. Perhaps this commendable silence, this resistance to celebrity, only encourages my drive to be let into the inner sanctum, to know what your works are really about. Given the circumstances, a meeting of our minds remains severely unlikely. In the epically embarrassing mould of Kraus and her antecedents, then, a love letter seems the only way.

Have you noticed that people aren’t really into drama in the way they are into other genres of literary fiction? Dramatic form is a strange outsider. Though we proclaim our preferences for formal experiment and hybridity, playtexts are unlikely to be seen as doing that work. On our overflowing bedside tables, they are nowhere to be seen. Given our ever-growing appetites for hybrid, bodily fictions and affective impulses, I think drama might declare itself newly generative. Alexander Zeldin’s The Confessions, which enjoyed a European tour last summer, is arguably a sign of things to come. I doubt any of this matters to you, a long-term eschewer of the cool. I’m much more superficial. I want to know why we aren’t reading plays, photographing their covers, raving about their formal possibilities. Why aren’t we fawning over Mojisola Adebayo, or debbie tucker green, or well, you? Is drama too much equated with over-thumbed classroom copies of Tennessee Williams, attempts to grapple with iambic pentameter, and other long suppressed efforts at youthful amateur dramatics?

Tradition and formal constraint dominate our understanding of the form. Three acts, realistic dialogue, easily ascertainable characters and plot, an insular unity of time and space. In Britain, the legacy of mainstream theatre must take some of the blame for unimaginative expectations. It is a legacy more entangled with cosy interval ice-cream consumption than subversive experiment. In your work, though, the discomfort of expectations and rules often provides a vital spark. It is the very prescriptiveness of dramatic form that carves out space for magical riposte. Only when we think we really know something can that thing be pulled like a rug from underneath us. I don’t know if anyone has told you this before, but you’re particularly good at pulling rugs. I suppose this is where I make a small confession: I’ve never seen a Caryl Churchill play. But I’ve read them all! I promise. Reading a play is a distinct and critically undertheorized experience, but it remains one worth having. Let me make a case for the value of it, and I suppose Caryl, a case for you, too.

Most people would know you from Top Girls, your anticipatory answer to the first glimmers of girl-boss feminism. The first play of yours that really spoke to me, though, was Fen. If Top Girls is the high-pop glamour of the neon shaded eighties, I see Fen as its muddier, weirder, older sister. There, you tell the stories of the women working the Cambridgeshire fenlands, of how poverty and suffering can be cyclical, and how desires persist even in the hardest, dirtiest landscapes. Top Girls, and then later, Serious Money, are both plays about corporate ambition and the seductions of finance, but to me Fen harbours the most powerful of critiques. It emphasises suffering, sweating bodies, and their ultimate indispensability. Someone, somewhere, is working under unlivable conditions to make your life comfortable. That’s what Fen is all about. That, and ghosts. Embodiment is always implicitly central with drama, but in Fen it is denied an inevitable emancipatory possibility. The body is not inherently radical, in fact its very presence is constantly interrogated. That’s another reason why I see your work as interested in textuality, Caryl, you present the body, literally on stage, but you’re also always interested in its absence. Isn’t that a heightened version of a dilemma at the heart of all feminist writing? Bodily and beyond. How to be both? In Fen, the working-class women of history are both there and not, felt and painfully absent. Only through the form of the ghost can they be given a voice. It’s as if you recognise rationality itself as historically equated with violent, capitalist and patriarchal logics, and appeal, as Silvia Federici famously did, to the witchy and enchanting as an alternative epistemological mode. That’s not to say women must abandon rationality entirely, but that sometimes the freaky and fragmented are the best tools for the task. Sometimes, things need to get weird.

What is it about irrationality that so appeals to you, returning to it again and again? Is it a response to the obvious absurdism of so much of contemporary life? Or the supposed hyper-rationality of the majority of institutional responses to impending crises? The Skriker is a play about irrationality, too, and there’s no doubt that it can be an affective tour-de-force in performance, but I’m thinking, as usual, of words. Of the long, tricksy monologues you give to your shapeshifting Skriker. There, you’re a master of intricate constructions and indulgent Joycean play, but it’s a mastery that can only be fully appreciated as a reader. The same goes for your use of deep-buried folklore and myth, from the Gaelic Kelpie to the Bogle. A richness of intertextuality, drawing on an ancient fabric of reality as a means by which to point to the rips in our own. They could be hard to pick up on in performance, but it’s all there, a gloopy pool of references, ready to be dived into whenever we pick up the text.

Many consider Far Away to be your masterpiece, perhaps because it takes questions of environment and irrationality even further. You give us just three characters, two of them shown working at making increasingly extravagant hats. They’re proud of their hats, it seems, but then you drop a bomb with a single line. ‘It seems so sad to burn them with the bodies.’ Pure, gross, horror. Our ears are pricked, we’re frothing with questions, but in performance there is no time to go back and reconsider. Here, the reader really matters too. Who could read a stage direction like:

The Parade. Five is too few and twenty better than ten. A hundred?

Next Day. A procession of ragged, beaten, chained prisoners, each wearing a hat, on their way to execution. The finished hats are even more preposterous than in the previous scene.

And claim that it’s not in part constructed for its reader? When that direction is acted, it’s likely stupefying and harrowing. To see so many physically vulnerable prisoners on the stage at once is, as Siân Adiseshiah has written, to be reminded of particular historic instances of state violence and suffering. To read that stage direction might well have a similar impact, but it’s also to be reminded of your admirable audacity Caryl, its comedy and its power. A hundred? Who else could make such an impractical staging so confidently casual? Who else, dare I say, would have the theatrical balls? Yet the bringing on of a parade of prisoners wearing flamboyant hats, for a scene lasting a maximum of a couple of minutes, is exactly what Far Away is all about. It’s as if it’s asking: how ridiculous, how absurd does suffering and ecological breakdown have to be, before we might allow it to affect us, before we might start to take it seriously?

I suppose I keep coming back to feelings. Not mushy, but fractious and deep. That’s what I love most about your work, and that’s why Escaped Alone is my favourite. There was a lot of speculation that its premise (four elderly women sitting in a garden, discussing their lives amidst revelations of apocalyptic chaos) was partly inspired by your own entry into late life, and contemplation of the fact. I’m not so sure about that – is personal experience the only reason why we might want to dive into the psyche of the older woman? What if she just happens to have interesting things to say? She does, of course, and the play is a tribute to that. What a novelty to have funny, fleshed out, post-menopausal women, commanding from their garden chairs, front and centre on page and stage. Their conversation ranges from the mini-Tesco to drone warfare: a particular kind of realism that recognises the absurd surrealism of life as we know it. Absurdity continues with Mrs J’s ferocious monologues. She describes financial markets as ‘floating’ or ‘hot’, darkly transformed into painful possible futures, where bodies drown and burn under market pressure. What I really love is not this well articulated critique of financialisation as Frederic Jameson foretold it, but the root of that critique as felt, ordinary, and compatible with the seemingly minor. Apocalyptic feelings are never far from the ordinary terrors the women describe in their own lives. Lena is agoraphobic, Vi struggles to breathe until the kettle is clicked in the morning. The women are defined by the negative affects that dominate their domestic lives, as well as by the global terrors that Mrs J evokes in their midst. It’s as if you’re staging the connection that Kathleen Stewart theorised between large-scale structural shifts and their everyday, almost imperceptible manifestations. For Stewart, the totalising descriptors of our political moment, words like neoliberalism, globalisation, or financialization, ‘do not in themselves begin to describe the situation we find ourselves in’. Instead, those realities are best felt at the level of the ‘weighted and reeling present’, in the ordinary feelings of ordinary bodies. Isn’t that all we have? Maybe it's time we got comfy with that fact.

Then there’s that strange part at the end of the play when Mrs J repeats the same two words, ‘terrible rage’, twenty-five times. On the page, that speech becomes an exercise in linguistic futility. We probably don’t even bother to read the words all twenty-five times. Who would? I think you know this, Caryl, and I think you’re interested in it, too. Why remind us, right at the last moment, of the inadequacy of words? You put the question in our minds: how much can the playwright really do? Articulating a meaningful response to the horrors the play has spoken of suddenly feels impossible. Theatre, and language itself, seem to temporarily buckle. Then, Mrs J stops, and with the line ‘and then I said thanks for the tea and I went home’ the play ends, a gesture to the significance of domestic life, inseparable from structural violence, but perhaps an admission of failure, too. We’re back in an overly comfortable bourgeois mode, the mode of cosy ice-cream consumption, remember? The institutional limits of language and literature are not only referenced, but shown to win out entirely. To bastardise Kraus then, Caryl, deep down I feel you’re a total cynic too!

In which case, the really amazing thing is that you’ve kept going – and that’s not meant to condescend. It’s just that Escaped Alone isn’t the only of your works to reference its own futility, in fact it seems almost like a career-long preoccupation. This impossible balancing act reminds me of a question you ask at the end of Far Away: ‘who’s going to mobilise silence and darkness?’ We need to reconcile futility with a vital need to conceptualise and discuss, if we’re going to confront the existential challenges facing us. And of course, words are never enough. But you’ve still kept writing, experimenting, attempting to articulate. Isn’t that the only way? To continually do so via the duality of the playtext is to prioritise a form where we might push the body to its representational limits, and question the political efficacy of language and affect as we go. I can’t think of better bedside table material. I might still not know what your plays are really about, I might not know exactly how they make me feel, and I might not know what they can do in the world, but I’m reaching for answers as I go. In this, your work is wonderfully writerly, as Barthes would have it. It’s all about doing, continually grasping, the work as an active experience.

Are you still there Caryl? Keep going! I think I hear you say. Perhaps it doesn’t even matter if that voice is all mine.

Onwards, then, with love,

Jennifer x

Jennifer Jasmine White is a writer and researcher based in London. She has degrees from Oxford and Cambridge, and is currently completing a PhD at the University of Manchester. Her research focuses on the relationship between working-class women and experimental forms, and she is always keen to write about art, gender, and class. You can find more about her work at www.jenniferjasminewhite.com.